Cellar

and works

On the outside of the cellar there is the external processing line, with the hopper where grapes are put, in order to fall into the crushing and destemming machine. At the end there is the press, in which we put directly entire grapes for malvasia “Piume”, or use later for reds, during racking.

Inside the cellar, at ground level, we have the area devoted to wine making, with stainless steel tanks, were we put must and skins and process the wines.

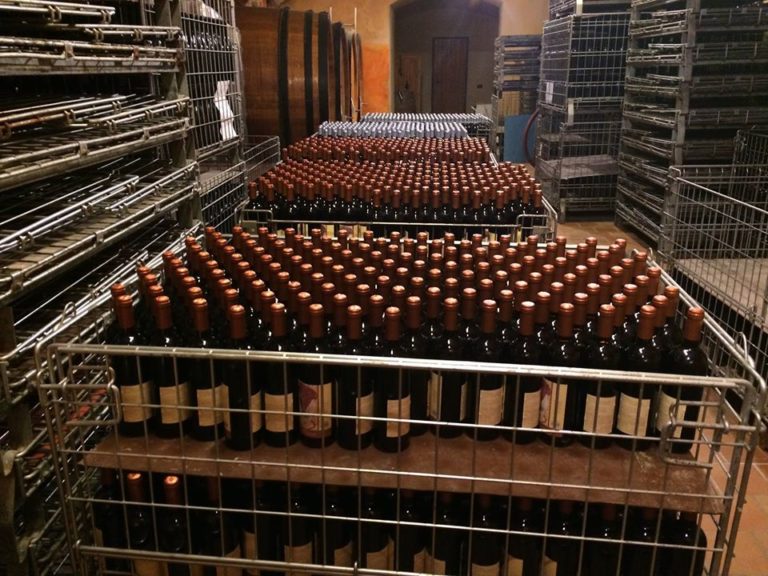

With a few step up we get to the bottling line, with filling, corking and labelling stations. We do these operations separately as the bottles are kept “naked” in steel cages, in the downstairs cellar and labelled and boxed only in small quantities or for specific orders.

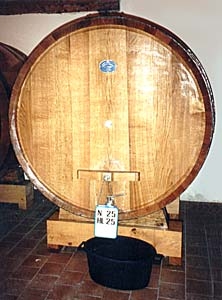

To the lower cellar it is possible to get by stairs or by a large elevator, with which we bring down the cages of bottles. This cellar is an old structure, with a vaulted brick ceiling, and keeps a constant temperature during the different seasons; it is employed for storage and aging. To this purpose, we have four french oak barrels of 25 hectolitres capacity, and some french barriques (allier wood).

The main difference is capacity (barriques are slightly more then 2 hectolitres) and that barriques are toasted (from light to strong), while barrels are not. Ours have been in use a long time, so their influence on the wine is much reduced.

From the beginning the winery has had a simple approach, aimed to still red wines. We do not use refrigerators, autoclaves, pressurized bottling, or other elaborate stuff.

Apart from our stainless steel tanks, which are a guarantee for cleanness and a certain level of sterilization, we have a simple pump which has assisted us loyally through the years, another smaller one employed (when necessary) for a slight filtering, a carton filter (cartons are paper squares, thick and uneven, through which wine flows), a steam cleaner, and little else.

Apart from these basic things, in the cellar there are the two of us, probably the best equipment to closely follow the correct development of our wines.

Our work

In the cellar as well work is endless; after vintage and the first phases of winemaking, there is always bottling and labelling.

All tasks are performed personally by us; we believe that it is very important to maintain direct control of what happens to our wines, in all stages of their evolution.

Whites and reds follow different paths.

Malvasia “Piume” grapes are put directly in the press and to the cellar arrives only the must, which is decanted after a night rest, cleaned of the deposit formed on the tank’s bottom and left to ferment until dry.

Obviously it is not left alone, but followed step by step, according to its necessities.

Malvasia “Dedica”, left to macerate on the skins, is treated almost like a red wine. Crushed and destemmed, needs a good maintenance during fermentation, in order to keep the top layer always wet. When the wine is dry, skins fall to the bottom of the tank and this is filled up. “Dedica” will stay like this until it is raked, months afterwards.

Reds go another way. Grapes are crushed and destemmed and must and skins arrive together to the cellar, where are put in tanks (not filled up), according to the variety and the plot they come from.

Alcoholic fermentation begins and the wine’s yeasts start to transform sugar into alcohol.

During this time, there is a lot of work involved with keeping down the top of the emerging skins, which are pushed up by the process, and have to stay always wet and submerged. Must is taken from a bottom tap and, with the help of the pump, is made to fall back from the highest place above until the skins are entirely covered again.

This must take place at least once a day for each tank. Alternatively, you can decant all the must in an empty tank, leaving the skins to drip, and then pour it back from the top. This is called a delestage.

The aim of all this chores is to extract all the best components from the skins and keep lies active and well oxygenated.

It is a wonderful time; the must is slowly fermenting, almost simmering, the tanks have warm bellies and throughout the cellar floats a deliciously tepid smell.

The morning, getting in, it is advisable to let all the carbon dioxide dissipate (it is a by product of fermentation and truly dangerous), without excessively cooling the cellar and disturbing the musts in this delicate moment.

When the young wine shows a fine colour, an adequate amount of tannins and coherent analytical data, it is drawn away and the skins are put into the press: it is racking time.

Press had 6 cycles; we never go further than the second one and stop very early in the process. Our damp skins, which by law must be brought to the nearest distillery, are easily recognizable.

Racking brings to an end the first part of work after vintage, the more active and chaotic.

The would-be wines (finally clean), after blending based on type, affinity and complementary features, are put in tanks filled to the brim, to complete the first part of their development, which will be finished after malolactic fermentation.

This transforms the malic acid in lactic, which rounds up and adds body to the wine, decreasing acidity.

Better leave the wines alone, to work well on their lees, until the fermentation is completed.

At this stage too the wines are followed analytically, to confirm or correct the impressions of tastings; one has to be very careful about possible faults or lack of balance. They are decanted one last time before wintertime, during which the cellar will tend to grow cold and they will further evolve.

Red wines meant to be aged are moved to the barrels or barriques in the cellar downstairs. It remains at a constant temperature all year long, and there they will stay during all their life before bottling, always undergoing periodical checks and decanting.

For young wines, when winter is over and spring well advanced, we start thinking about bottling the withes, and eventually some reds.

Filtering is always very limited, to give the young wines a shine.

Reds aged in wood need none, having had already a long while to clear. A finishing touch to exalt colour and structure is sufficient.

At bottling it is added the minimum quantity of sulphites (well below the one established by law), only to keep the wine whole and healthy.

Afterwards, the wines go to the lower cellar, for stocking and improving with time, waiting for the right moment to be labelled, put on the market, and poured into your glass.

Another important character

Who makes our wines? Us, obviously, at least the manual side of it. And we also think about what we want them to become. But there is another essential character: the oenologist.

Sometime these experts play their role more on the mediatic plan than the real one.

Some of them follow a thousand fold of different winery on the national territory and beyond, and they can “do” or “undo” a producer’s reputation.

They may behave as owners, believing their presence will be a valid pass for wine guides and markets. Often it is just hurried advices, or the same recipe is used for different products in different areas, with no respect for grape qualities, territory, or the producer personality and beliefs.

We too, at Martilde, had a proper dose of stories more or less good, but, while we have tried to reach a certain degree of autonomy in many aspect of our work, regarding wines we strongly believe in the contribution of an external expertise.

You need a certain amount of detachment and objectivity, a treasure of practical experience and knowledge, plus the capacity to cleverly compare what is happening in your winery with what happens elsewhere.

If, to all that, you add the gift to smile and make others smile, curiosity and imagination, you get Giuseppe Zatti, who also became a dear friend.

Beppe has equal attention to the vineyard and the cellar, knows and love the area, and keeps together the will to try new roads and the wish to never forget our identity.

The wines and we are very happy to have found him.